HIROTAKA, Fukui

“You won’t need science once you’re out in the real world,” my grandfather once said as he leaned back in his chair, grease still darkening the skin beneath his fingernails. He had spent his life driving trucks, moving goods along highways he could navigate without maps. To him, knowledge was what kept an engine running, not what filled a book.

A few years later, I remember stepping into the office of my other grandfather. He wore a crisp suit and kept leather-bound books stacked behind him like a second wall. He had a university degree and had risen to become a company president. His hands were clean, his words polished, and his presence always slightly distant—like someone who had spent a lifetime mastering the art of being listened to.

These two men never met if my mother had not married my father. They live together in me. One gave me the sense that life is earned by labor. The other, that life is claimed by knowing which door to knock on.

My mother was the daughter of a truck driver. She graduated from high school and went straight to work. She never went to college, not because she wasn’t smart, but because there was never enough money or expectation. My father, on the other hand, is the son of the company president. He holds a PhD, studied abroad, and spent years as a researcher in the United States. Their marriage was not just a union of two people—it was the quiet collision of two worlds.

I grew up in the in-between. I went to university. So did my brothers. Two of us are pursuing doctorates, continuing the academic path our father began, while born to a woman who never had the chance to walk it herself.

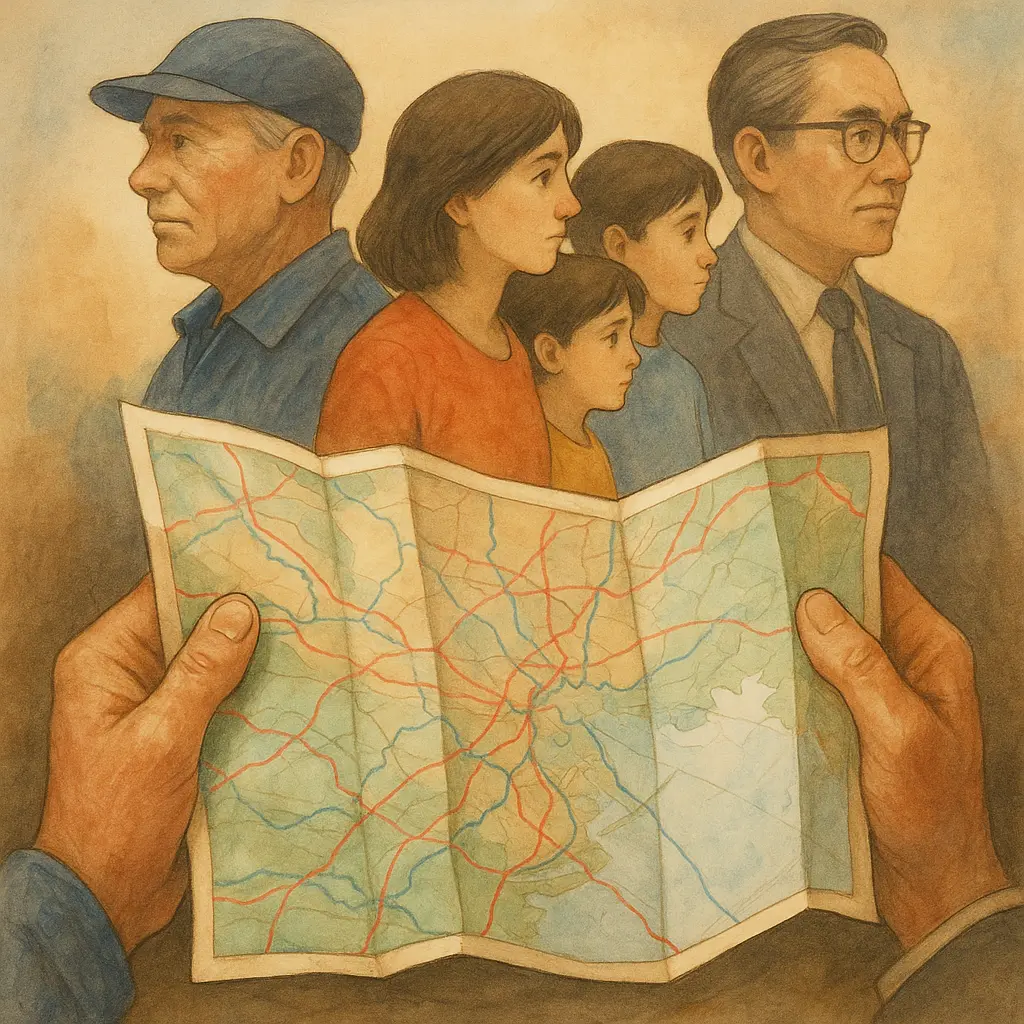

This is an essay about that inheritance—not of money, or land, or even ambition, but of maps. The ones we are given. The ones we never see. And the ones we draw for those who come after us.

My maternal grandfather never spoke about books. He spoke about oil changes, faulty spark plugs, and road fatigue. He had a thick, sun-darkened neck and hands that looked like they belonged to the road itself—cracked, calloused, always stained with something. When I was a child, I thought he was a kind of magician, someone who could fix anything with his hands. I didn’t know then that what he fixed, day after day, was survival.

He left school at fifteen. There was no choice. His father drank too much, and the money never stretched. He became a truck driver, moving heavy things for men who owned lighter lives. He drove long hours, silently ate the meals his wife had made. He came home with his back aching and his eyes dulled. I never heard him complain. But I also never heard him dream.

My paternal grandfather, by contrast, lived in a house with heavy curtains and polished floors. He had gone to university at a time when that still meant something sacred. He read newspapers in silence every morning, sipping coffee that smelled like importance. His office smelled of leather, dust, and distant places. He became a company president. When he spoke, people listened—even if he said nothing new.

I remember once sitting at his feet, looking up at the rows of books behind him. I couldn’t understand the titles, but they looked powerful. I asked him once if he had read them all. He said, “Not all of them. But they belong here.”

The two men shared almost nothing. One drove trucks. The other sat in boardrooms. One learned to be quiet because there was no space to speak. The other was taught to speak because people were always ready to listen.

Yet both were called “Grandpa.” Both gave me sweets in secret. Both smelled of something warm and familiar. One like engine oil. The other is like old tobacco and cedar.

Looking back, I realize their lives were shaped by more than personality or effort. They were shaped by class, opportunity, and education—words I didn’t yet have when I watched them live out two radically different versions of manhood.

One taught me the dignity of labor. The other, the luxury of command. Between them, I learned that life does not begin at birth, but at the starting line we are placed upon.

My mother never spoke of college—not because she didn’t want to go, but because she was never taught to expect it. In her family, graduating from high school was enough. More than enough. It meant you had made it through without dropping out. It meant you were ready to work, to earn, to help.

Her older sister followed the same path: high school, then employment, then marriage to a man who worked with his hands in a small auto repair shop. Their lives were patterned not by desire but by necessity. They learned early that dreaming without means only made the air heavier.

I remember once asking my mother if she ever regretted not going to university. She smiled, gently, and said, “I never had time to think about it. We just... kept moving.” There was no bitterness in her voice, just a practiced quiet—one I now recognize as the mark of those who have learned to want less because they were never offered more.

On the other side of the family, my father's sister graduated from university. She carried herself with a kind of easy sharpness, as if intellect were not something to perform but something she could wear like a well-cut coat. She married a man who had also attended one of Japan's top universities, a man whose father had been a senior figure in one of Japan’s largest newspapers. He now writes for that paper himself, as its chief editorial writer.

Their marriage felt almost effortless. They spoke the same language—not just in words, but in worldview, rhythm, and reference. They laughed about books I hadn’t read and places I hadn’t been. When I visited their home, I felt as though I had stepped into a different grammar of living: everything was quiet, intentional, and refined without being ostentatious.

My mother’s sister lived not far away, but in another universe. Their home was filled with plastic storage bins and worn carpets, and the sounds of effort. The television was often on. Conversations circled bills, traffic, sore backs, and small blessings. The world there was narrower, but not loveless. Just heavier.

Both sets of women—my mother and aunt, my father’s sister—grew up in the same country, in roughly the same decades. But they did not grow up under the same wind. A current of expectation pushed forward one, while a current of survival drove the other.

Love, I believe, is real. But love is also structured. We do not fall in love with people at random. We fall in love with people we meet. And we meet people in schools, in workplaces, in social worlds that reflect who we’ve already been trained to become.

My mother’s sister married a man who reminded her of the world she already knew. My father’s sister married a man who reflected the world she had been groomed to enter.

There is no judgment in this. No one married wrongly. No one lived wrongly. But looking at them side by side—at their lives, their homes, their vocabulary, their air—I began to see how marriage, too, is a form of reproduction. Not biological. But social. Cultural. Quiet.

They didn’t marry into different classes. They married into their own.

My mother never went to university. She worked in accounting offices and administration jobs, the kind of roles where competence is expected but rarely praised. She was always early, always precise, always unnoticed by those who mattered. She didn’t read novels, didn’t quote philosophy, didn’t pretend to be what she wasn’t. But she carried our family.

She met my father—a man with a PhD, fluent in English, a researcher who would later spend years working in the United States—at a company gathering, where her quiet clarity must have struck something in him. Or maybe it was something simpler: she listened when he spoke, and he saw in her not ambition, but steadiness. They married, and in doing so, drew a line across two different maps. One was filled with books and degrees and the possibility of foreign cities. The other was filled with responsibilities, budgets, and the gentle burden of self-restraint.

I often wonder what it felt like to enter a world that had never been meant for her. To sit at dinner tables where conversations swirled around research, global news, and university gossip. She rarely joined in. But she always remembered what everyone had said. She carried the whole room in silence.

She never told us to study. She just created a world where we did. There were no bookshelves filled with classics, but there was space. There was time. There was warmth, and food, and unwavering belief in our potential—even when she didn’t use those words.

My brothers and I all went to university. Two of us are now in doctoral programs. We moved into a world my mother had never inhabited, but somehow made possible. We applied to universities using English in the entrance exam, which she didn’t speak. We wrote research papers that she couldn’t read. We moved among scholars and thinkers, while she packed our lunches and reminded us not to forget umbrellas.

And yet, no one shaped our futures more than she did.

My father gave us the path. But my mother gave us the ability to walk it. Her restraint taught us discipline. Her silence taught us to listen. Her compromises made our choices possible.

In academic discourse, there’s a term: “social reproduction.” It refers to how class, education, and privilege are passed from one generation to the next, often invisibly. But no theory quite captures what it means to be the one who interrupts that chain, not by revolting, but by making space. Not by rejecting the past, but by refusing to limit the future.

My mother is not a break in the chain. She is the joint. The quiet seam where two worlds, two logics, two dreams meet.

Sometimes I wonder if she felt lonely, standing on that seam. Between families who didn’t quite understand each other. Between children who would go further than she had, and a childhood where going further wasn’t even imagined. But she never complained. She just kept things moving.

When I think about inheritance now, I don’t think only of bloodlines or degrees. I think of her. Her hands were folding laundry late at night while we studied. Her careful saving of bus fares. Her quiet decision to carry a different kind of burden, so we wouldn’t have to.

She was never given the map. But she built the road.

All three of us—my brothers and I—went to university. Two of us continued into doctoral programs. On paper, we appear to be the kind of family that values education, believes in books and ideas, and appreciates effort. And in many ways, we are.

We studied hard. We got good grades. We passed entrance exams, sat in lecture halls, and wrote thesis papers deep into the night. From the outside, it appears to be merit. Like drive. Like success earned by discipline.

But sometimes I wonder: how much of our path was chosen by us, and how much was chosen for us—quietly, long ago, by people who would never read the essays we now write?

My father never said, “You must go to university.” He didn’t need to. He said that both pursuing higher education and entering the workforce were matters of individual freedom.

The books we read, the dinner conversations, even the tone of his questions—all of it nudged us toward university.

My mother never asked about our grades. But she created the conditions for studying—safety, silence, and a meal waiting. She didn’t push us, but she cleared the road so we could run.

I used to think I worked hard. I still believe I did. However, I’ve come to understand that hard work only becomes successful when the soil is already fertile. We planted seeds in the ground that generations of sacrifice, planning, and quiet privilege had already tilled.

On my mother’s side, no one had gone to university. Not because they lacked ability, but because no one had time, money, or expectation. My mother and her sister followed the lives they were born into. No map was ever handed to them. They moved by instinct and necessity, not by vision.

On my father’s side, education was not just encouraged—it was woven into identity. My father earned a doctorate. His sister married into an elite journalistic family. They spoke a language of references and fluency, one that I absorbed without even realizing I was learning it.

This is what makes “education” such a misleading word. We often think of it as a ladder, but for many, it is a hallway with locked doors—and only some of us are given the keys.

I didn’t open those doors with brute force. I was shown where they were. I was taught the handle would turn. I walked through them not because I was exceptional, but because I was expected to.

And once you are through, it becomes very easy to forget that many others never even saw the hallway.

When people talk about “earning” their place, I think of my mother. Not because she earned her place in the academic world—she didn’t. But because she earned ours. Not with grades or credentials, but with the invisible labor of belief.

My father gave us the structural map. My mother permitted us to follow it.

I carry degrees now. I read theory, attend conferences, and speak in rooms my grandparents never imagined. But part of me is always aware that I did not build this from nothing. I built it from everything they were.

So when I say I’m educated, I no longer mean I’ve read certain books or passed specific tests. I mean that I was given space to think, people who believed I could, and the unspoken comfort of knowing that if I stumbled, someone would catch me.

Is that education? Or inheritance?

I carry many things. Some you can see—degrees, certificates, polished words. Others are quieter. Heavier. Less easily named.

I carry the silence of my mother, who never asked for anything and yet gave everything. I carry the hands of my maternal grandfather—calloused, strong, uncelebrated—who worked long before I was born so I could write in rooms he never entered. I carry the presence of my paternal grandfather—distant, formal, full of expectations he never spoke aloud.

I carry the soft assurance of being told, without words, that my life could be large.

There are things I have earned, and things that were given to me before I even knew they were gifts. A stable home. A bookshelf. The belief that time spent reading is never wasted. And I carry the guilt of that inheritance, too, not because I did anything wrong, but because I know others worked harder with far less and were not allowed to arrive where I stand now.

I carry the tension of being in-between. Between two family lines. Between two ways of living. Between two languages—one spoken in journals and lectures, the other in bills and grocery lists. I learned to navigate both, switching tone and tempo, learning what not to say in each world. In some rooms, I hide my origins. In others, I feel like a visitor in borrowed clothes.

When I was younger, I believed education was an escape. Now I understand it as inheritance, dressed in the costume of freedom.

I carry a fear, too—that I might forget. That in chasing progress, I might become blind to the hands that made this possible. That I might one day speak only in the polished cadence of privilege, forgetting the crackling silence of my mother’s side of the dinner table.

I carry my name. I carry my grandparents’ lives inside my posture, my choices, my sense of what is possible. I carry their contradictions—the pride of self-reliance, the shame of not knowing enough, the stubbornness, the quiet endurance.

And I have questions. So many questions.

What is success, if its foundation is uneven?

What is choice, if the options were laid out by someone else long before you arrived?

What do we owe to those who came before us, and to those who come next?

These are not academic questions. They live in the body. They surface in moments no one sees—when I hesitate before speaking, when I write a sentence I’m not sure I have the right to say, when I try to explain to someone who’s never had to think this way.

Still, I carry these questions. Not as burdens, but as reminders.

There is power in knowing where you come from. However, there is also a responsibility in knowing who cannot follow you. My path is not only mine. It is stitched together by those who stayed behind, who never got the chance, who made different choices because the world gave them different doors.

We like to believe that we carry only what we choose. But so much of what we carry is given to us by family, by class, by silence, by love.

And maybe the most honest thing we can do is not to pretend we earned it all,

but to carry it well.